‘I have to go away for a while,’ he says. ‘But I want to tell you how much I’ve enjoyed spending time with both of you.’

‘What?’ asks the woman, brow furrowed.

‘You’ve made my heart so full,’ he says.

‘What are you saying?’ she asks.

‘We’re a family,’ he says to them both. ‘Dougie… I mean… I will be back.’

‘You’re not… Dougie?’ she says.

‘What? No!’ says the young boy. ‘You’re my dad.’

‘I’m your dad, Sonny Jim,’ says the man. ‘I’m your dad, and I love you. I love you both.’

The man brings the woman and child close to him, embraces them.

‘I have to go,’ he says. ‘You’ll see me soon. I’ll walk through that red door, and I’ll be home for good.’

The man stands, walks towards the exit.

‘Don’t go,’ says the woman.

‘I have to,’ he says.

They kiss.

‘Whoever you are,’ she says, ‘thank you.’

The man walks way, leaves the casino.

*

Gathering my thoughts before leaving Brussels, the city I’ve called home for the past 25 years, I’ve been drawn magnetically to this episode of an American TV show. Each time I watch the scene, it reaches a hidden chamber in the very core of me, unlocking a door, revealing some part of my true self. When I tried to explain it to an old friend last week, I choked up before I’d even started.

What’s going on?

The show is Twin Peaks. The scene, ‘Farewell’, arrives in episode twelve of the third and final season, which David Lynch wrote, directed, and starred in. Spanning twenty-five years and as many lives in a small rural town, Twin Peaks brings Lynch’s surreal but intimate dreamworld to the small screen, a masterpiece of modern television.

It also retells one of humanity’s oldest stories: our yearning to find the way home. In the casino, Lynch opens a portal between domestic melodrama and ancient myth, between Las Vegas and the cosmos. The family crouching among the twinkling slot-machines might just as well be Homer’s gods, speaking among the stars. The question here is not whether the father is coming back, but whether he is the father at all. Who is he, truly? And who, then, are we?

As I empty the drawers and pack the bags containing a quarter-century, one half of a life, I ask myself: did I truly live here, in this city that worships free movement? Did I put down roots and make it a home? I’m haunted by the words of many friends who doubt we could ever lead a ‘normal life’ in Brussels, where everything is transitory, ephemeral, uprooted. Looking back on twenty-five years, have I merely been passing through?

Memory tells a different story. Love and friendship have grown in these streets and bars, kitchens and bedrooms. If you’re reading this now, you’ve probably become a voice in my head, a voice that I turn to in the small hours, a voice that follows me wherever I go. I confess now that I’ve impersonated you over many years, imagining what you would say, to help me find the answers, and I can only hope you’re not offended.

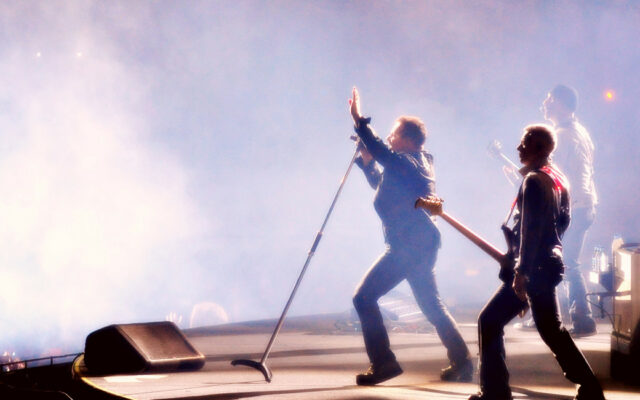

Music tells another story. With you, I’ve watched hundreds of concerts in one of the world’s greatest venues, the temple in our city, refuge to the travelling gods, the Ancienne Belgique. At the back wall of the foyer, a panel displays the names of thousands of bands who’ve played here over three decades, remembering the heroes that fight our invisible demons. I stood here in March 2016, the night after our city lost 40 people to a terrorist attack, and I felt safe.

To walk from here, after the show, towards the Archiduc, an art-deco bar that transports you to the deck of a 1930’s steamliner, with its piano, brass plating and balcony, is to move along our city’s nocturnal nervous system, towards a cool gin and tonic with cucumber, and perhaps a sight of the band. The Archiduc has multiple selves: sweaty Motown disco on Saturday night, hushed shrine to jazz on a Sunday afternoon, midweek refuge for a weary soul, home to everyman.

Brussels’ night-temples all pass the New York test: that city of cities has nothing better than we have, it simply has more of it. On these sticky floors I lived the moments that punctuate a human life, making vows, sealing friendships, straining on tiptoe to the stage, each event reshaping me and, I hope, making me part of the furniture, so that one day my ghost may haunt the chairs and tables, look down on the dancers, whisper words of encouragement into the ears of a shy young man.

The love of music, its perpetual emotion-machine, a magic box that takes our joy, yearning, and grief, encoding them into chords, voices, and beats, so that our own turmoil becomes one with the sound, starting a new conversation between us and the singer, has also built a home for me. Whenever my neural pathways hummed with the sound of a new album, my body was sat on the same part of the sofa, drinking in someone else’s tears so that I could purge my own. I might have done this anywhere, but I did it here, on this sofa, and this too has been a home.

Then the walks we walk every day, ploughing our furrow deeper into the earth, our daily routes like the lines on the back of our hands, unseen and unchanging. These were the walks that told me it was time to go, when I started seeing ghosts on every corner, beckoning me to relive a scene. But those paths are part of me too, they’ve hardened the soles of my feet, chipped away at the joints in my knees; tons of car fumes have blackened my lungs. This too is home.

Like the man in the Paul Auster story, I’ve endlessly followed a circuit that spells out a message: down the dusty grey canyons of the European quarter, its offices camped along a city-centre motorway; the underground to Midi station, more international than any airport, its shoppers weighed down with a week’s worth of fruit and veg; the weekend jog around the Bois de la Cambre, the path rising at each end of a miniature lake, and then out into the Forêt de Soigne and the deer startled on a night run; the network of Irish pubs where, in the poetry of justice, I’ve watched countless English defeats on foreign football fields; the squares at Châtelain, Saint Boniface and the Sablon, all beautiful, all unforgivably stained by the country’s addiction to the car. Each route a new wrinkle round my eyes, all now part of me too. I will always be able, in my head, to walk down every street of my hometown, Nottingham, and now Brussels will occupy a similar space. My mind downloads no map – it is the map.

And yet, all these roads and rituals, squares and temples, have not truly built a home, not the one that matters. This is what the scene in the casino is telling us: we don’t find home in the streets and houses where we’ve lived or the habits we’ve followed, or the sofas where we’ve shared embraces and shed tears, but in the love we’ve built with family and friends. Our true odyssey takes us to the space between each of us, a place that can seem a sea of loneliness, an unbridgeable divide, but one into which we set sail each morning, in a bid to get a little closer. Our endless home-leaving is made bearable only by the possibility that we might take our friends with us – inside our minds, inside our memory.

The treasure of my 25 years in Brussels is the sediment of countless conversations, every coffee and sandwich a brick in a home I share with friends. Just as we are not and can never be a single, unified self, nor can we build and keep only one home. Each of these homes, in our native town and then in the places we discover, is a place where we feel at ease because we can be ourselves, and we can only be our true selves through our relations with others.

So, yes, I have lived here, in Brussels, a normal life, whatever this means, and it was rooted in love and friendship. It has all been real; I will remember all of it: the drunken kisses; adopting l’Amour Fou as my first local, dancing till six in The Archiduc; binge-watching The Sopranos and The Wire; marriage and divorce, no kids, but then a friendship on firmer ground; eating the curry lunch at The White Horse on place du Luxembourg; shaking Bono’s hand outside the old Conrad hotel; listening to Forest play every Saturday, through thin and thinner; hiding the European Cup in my UEFA office; buying the Sunday papers from the Librairie de Rome; scoring with a volley from outside the box for Royal Brussels British Football Club; watching Arcade Fire walk and play through the crowd at the Ancienne Belgique; watching the sunset from the Palais de Justice, its scaffolding still in place after 25 years; getting to my office 15 minutes before terrorists set off a bomb at one of my metro stops; listening to Mahler’s second at Bozar and feeling my insides wrenched in all directions; kissing the head of my friend’s first child; waking up on the morning of 25 June 2016 and taking a photo of the garden because I just didn’t know what else to do; talking with our book group about whether we would die here; and then this life under lockdown with the sound turned off; but above all, and the most precious thing, the coffees, beers, dinners and dances with all of you, my friends – you are the one thing I will keep from it all. This is home.

What, then, is happening in that casino, when the father, or the man who says he’s the father, says farewell? Why does he thank them for the time that they, the family, have spent together? Why does the wife thank him – “whoever you are” – before he leaves? Because, like many of us, they are lost and untethered; he’s running from something, trying to find his way back home. The man – father, husband, impostor – is all of us, just as we are all his wife, and his son. We’re family. This is our story. We cannot know the other, not even the ones we love most, but we try, and we must. Because, at the end, this is the only true home that we have: each other.